Vanderbilt Charts Course for Championship Events

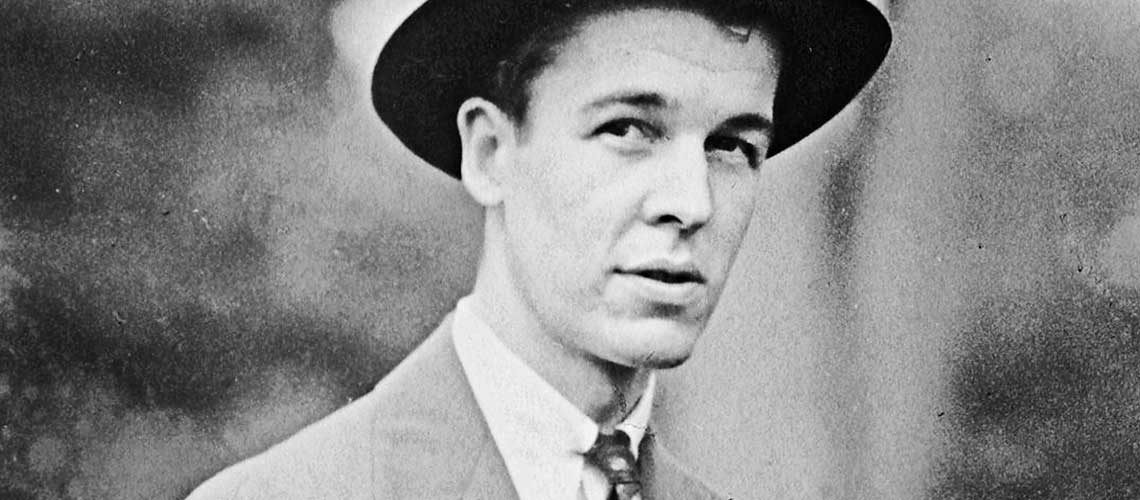

LAUREL, MD – At the ripe old age of 23, a horse crazy Alfred Vanderbilt Jr. got it in his head that he could create the definitive championship of thoroughbred horse racing in America. Wealth tends to beget confidence, or hubris, and Vandberbilt certainly had the wealth.

His plan was deceptively simple: Invite the best horses in training to Pimlico Race Course, in Baltimore, in November for a weight-for-age handicap at the Preakness Stakes distance of 1 3/16th miles.

“I want it to be what the World Series is to baseball, what the Rose Bowl is to football,” Vanderbilt told Time magazine in 1939, two years after the inaugural running of his new Pimlico Special and already, of course, an enormous success.

That same year, he said to the New York Times, “No entry fee. By invitation only. We put up $10,000 and a big gold cup, and the winner takes all. I’ve been trying to make this something like the World Series of racing. Get the best horses around for a big autumn classic.”

In its first year, the Special purse was only $7,500 – not a lot even in 1937, considering the Kentucky Derby that year put up $50,000 with a trophy cup worth $5,000, but Vanderbilt proved right, and (if you allow the debut as a one-year trial run) the race was pretty much an overnight sensation and became – with a long dormant period between its two brilliant incarnations – one of the most historic and important races in the country.

Essentially, what Vanderbilt had done was draw the blueprint for the Breeders’ Cup Classic, the centerpiece of American racing’s modern-day, year-end championship event. In 11 of its first 17 years, the winner of the Pimlico Special was named Horse of the Year (seven of the first 17 Breeders’ Cup Classic winners earned the title). Nine of those early Special winners are in the National Racing Hall of Fame. Six had won the Preakness. Four – War Admiral, Whirlaway, Assault, and Citation – annexed the Triple Crown.

When you toss in Seabiscuit, the fabulous filly Twilight Tear, and Tom Fool, the Special mirrors a pantheon of thoroughbred immortals.

***

Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt Jr. was born into the world in 1912, the year the Titanic sank, and three years later his father went down at age 37 with 1,194 other passengers on the British cruise liner Lusitania off the coast of Ireland, when a German U-boat sank it with a single torpedo and set into motion the calamity of World War I.

In the mid-1800s, Vanderbilt’s great-grandfather Cornelius Vanderbilt, known as the Commodore, was a towering, central presence in the development of shipping and railroading in the country, and his biographer T.J. Stiles wrote that he “helped to create the corporate economy that would define the United States into the 21st century.”

The family accumulated enormous wealth and created a dynasty.

In 1922, Vanderbilt’s mother, Margaret Emerson, took her 7-year-old son to his first horse race, the Preakness Stakes, which, that year, ran on the same day as the Kentucky Derby. The hook deeply set, and racing reeled in the boy.

Like many relatives, Vanderbilt went to Yale, but unlike many he never graduated. Emerson’s father, Isaac Emerson, was the enormously wealthy inventor of Bromo-Seltzer antacids. When Vanderbilt turned 21 in 1933, Emerson gifted him her late father’s Sagamore Farm, 600 acres of magnificent pastureland in Glyndon, Maryland. He developed it into one of the state’s premier thoroughbred operations until finally selling in 1986, breeding and/or racing top-class runners such as Discovery, Next Move, Bed o’ Roses and one of the finest racehorses of all, the “Grey Ghost,” Native Dancer, who won 21 of 22 lifetime starts, and whose only loss came in the 1953 Kentucky Derby.

By 25, Vanderbilt was worth an estimated $20 million, which in today’s money, factoring in inflation, is about $421 million – no Elon Musk, but back then a single filer making $100,000 a year paid 62% in federal income tax and today it’s 24%.

Now, the richest of the rich fly their own rockets into space; Vanderbilt, however, took his money, bought Pimlico, and soon made himself president. Later, he became president of Belmont Park, as well. There would be many more titles to come, all in the service of his passion for racing.

In the summer of 1937, there was no indication the Pimlico Special was about to arrive. Vanderbilt had promised a “stakes-a-day” policy for the fall race meet at Pimlico, which ran from Nov. 1 through 11. Yet, in the July issue of the Maryland Horse magazine, the race was not among the Pimlico Autumn Meeting stakes posted by M.L. Daiger, racing secretary for the Maryland Jockey Club. Same with the August edition, with the $3,000 Lady Baltimore being the only stakes on the schedule for Nov. 3.

In fact, the Maryland Jockey Club didn’t announce the new race until Oct. 24, according to an issue of The Sun newspaper the following day, in “response to the request of horsemen for a good 3-year-old stake on the fall program which has been missing for a couple of seasons.”

One of those invitations, however, started the wheels turning and hoofs churning because it was accepted by Samuel Riddle, who owned War Admiral, a son of Man o’ War, whose shadow loomed large over racing and was the horse widely considered the greatest who ever lived.

War Admiral did not stand 16.2 hands like his gigantic father but was a sleek racer, cantankerous and fast. In the Kentucky Derby that year, he raised a fit at the starting gate then led the entire way to easily beat Pompoon, the 2-year-old champion of 1936. A week later, War Admiral took the Preakness against just two opponents, again acting up, and then on June 2 he crashed through the starting gate several times before composing himself to take the Belmont Stakes and seal the Triple Crown.

Being ahead of the Preakness on the racing calendar, the Kentucky Derby had “priority” over the Preakness, according to the Blood Horse magazine, but “the promoters of the Preakness also had a few things to congratulate themselves upon. They had, for example, War Admiral’s owner, Samuel D. Riddle, who, too ill to attend the Derby, came with his physician to witness the Preakness; they had most of both houses of congress, an ambassador from Brazil and several dozen of assorted celebrities.”

Riddle preferred racing in Maryland and New York, and Vanderbilt believed he could get War Admiral for a showdown with the 4-year-old Seabiscuit, the rising rags-to-riches star in California, who had drawn 45,000 fans that March to Santa Anita Park to watch him smash the 1 1/8-mile track record in winning the San Juan Capistrano Handicap by seven lengths.

As author Laura Hillenbrand noted in her famed book, “Seabiscuit: An American Legend,” “In the latter half of the Depression, Seabiscuit was nothing short of a cultural icon in America, enjoying adulation so intense and broad-based that it transcended sport.”

Seabiscuit’s handlers, owner Charles Howard and trainer Tom Smith, headed east at the end of May 1937 to go big-game hunting for the best opposition they could find, and upon arrival their horse built on his renown, winning the Brooklyn Handicap, Butler Handicap and Yonkers Handicap.

In September, however, Seabiscuit finished third in the Narragansett Special in Rhode Island, struggling home over a muddy track, shades of things to come. He rebounded a month later with another win that moved him past War Admiral as the leading money earner that year.

A confrontation between the two sensations arose as possible for Oct. 30 in the $15,000 Washington Handicap at Laurel Park Racecourse in Maryland, but Seabiscuit was pulled because of a sloppy track, and War Admiral easily galloped to victory in his first try against older horses.

The following day, The Sun newspaper splashed a front-page headline in a gigantic font size nowadays reserved for the end of the world: “War Admiral Wins Before 22,000.” The reporter of the story could not contain himself, gushing that War Admiral “definitely stamped himself, not only as champion of his own division but the ‘horse of the year.’ Possibly he’ll be the ‘horse of all time.’”

Ultimately, the first Pimlico Special was not entry fee free or winner takes all. It cost horsemen $20 to nominate with a starting fee of $150, and purse money was paid down to fourth place. In fact, invitations only went out to 3-year-olds.

Perhaps it was fortunate a match against Seabiscuit hadn’t taken place – yet – because War Admiral’s long campaign that year had begun to catch up with him, and he was far from his best Nov. 3, just four days after his prior start.

Ten runners entered the first Special but only four ran. War Admiral was bet down to odds of 1-to-20 yet labored to get out of last place, and jockey Charlie Kurtsinger resorted to his whip even before the field reached the far turn. War Admiral would have lost had the front-runner, 26-1 longshot Masked General, carrying 28 pounds less than the favorite, not made a beeline for the outer rail in the stretch. War Admiral got up and got lucky. The $2.10 payout to bettors was the lowest in the history of Maryland racing.

The following day, in The Sun, Don Reed wrote, “There may never be another Pimlico Special, but this one will live a long, long while in the minds of the 15,000 fans who gathered to pay homage to the 3-year-old champion and remain to wonder whether he’s as good as they had believed he was.”

Interestingly, Seabiscuit did wind up racing at Pimlico that fall meet, eight days later on closing day, and he lost in the $10,000 Bowie Handicap at 1 5/8 miles to Esposa, a filly at odds of 15-1, who nailed Seabiscuit 20 feet from the line and won in a photo finish.

***

Seabiscuit and War Admiral continued their collision course waltz through 1938, racking up wins and building excitement wherever they ran. Racing then looked far different than it does today, when a horse like Mage can win the Kentucky Derby off just three career starts.

As a 3-year-old, War Admiral won the Triple Crown and just kept running.

“These horses, Hall of Famers, raced two or three times in a few weeks,” said Mike Veitch, historian for the National Racing Hall of Fame. “I believe as the years go by, their greatness really stands the test of time because of that.”

The only remotely comparable recent fever pitch and demand was the fan hysteria for a showdown between superstar fillies Rachel Alexandra and Zenyatta, which simmered to a boil in 2009 and 2010 yet never took place.

For a while, it seemed War Admiral and Seabiscuit would never meet either. Belmont Park planned a match race for Memorial Day, but Seabiscuit withdrew two days before because his sore knees were bothering him. Then War Admiral skipped the Suburban Handicap. Finally set to meet in the Massachusetts Handicap, Seabiscuit again was held back because of wet grounds.

On Oct. 25, 1938, The Sun sniffed about War Admiral and Seabiscuit, “the two have ‘met’ oftener without ever actually racing each other than any other pair of thoroughbreds.”

It took Vanderbilt, then vice president of the Maryland Jockey Club, to get it done, and, amazingly, for a purse of only $15,000.

“Neither owner was interested in the amount of the purse,” Vanderbilt told the New York Times. “When I asked about it, they said they didn’t care.”

This Special was winner takes all, and when it finally arrived on Nov. 1, 40,000 fans paid to get in, and the thousands more outside lined up 10 deep or simply knocked down the fences.

Both horses were at their peak. Jockey George Woolf sent Seabiscuit right to the lead by a length coming out of the first turn. Kurtsinger advanced War Admiral to challenge at the half-mile mark, and together they dogged Seabiscuit for three-eighths of a mile. By the eighth pole, War Admiral was done dogging. Seabiscuit drew off to win by four lengths and beat the reigning Horse of the Year.

The newspaper coverage that ensued was utterly intense. The Pimlico Special had arrived.

The following year, the 3-year-old Challedon made for a magnificent encore to Seabiscuit-War Admiral. He already held the world record time for a 1 3/16ths miles, earned in a race at Keeneland, and turned the table and toppled the undefeated Kentucky Derby winner Johnstown in the Preakness.

In 1939, 25,000 fans arrived at Old Hilltop (the actual hill, which long had plagued the view of fans in the grandstand, was dug out of the infield the prior year) to watch Challedon take on 4-year-old star Kayak II and Cravat. As Time magazine described it, with Hall of Fame rider Eddie Arcaro aboard, Challedon “began to run like a Halloween Hooligan,” and beat Kayak by a half-length.

The huge crowd broke out singing “Challedon, My Challedon” to the tune of “Maryland, My Maryland,” the state song, and the Special became even more special. Challedon returned and won the race again in 1940.

“The Special was unique from birth,” George Bernet wrote in the May 14, 1988 Daily Racing Form. “In fact, the Special WAS racing: the epitome of a sporting contest that had brought the thoroughbred sport unscathed through 200 years of war and revolution to prosper around the world. It was the first invitational race in the nation and the conditions of the early years embodied the sporting ideal: Winner-take-all purse and win betting only, no matter how many starters.”

Through the years, there weren’t many starters, only the best of the best. In its first incarnation, the largest field to contest the Pimlico Special was eight in 1955.

Seabiscuit-War Admiral is the most famous match race of all time, but the Special had five match races in its first 22 years. Two Triple Crown winners, the Calumet Farm stars Whirlaway and Citation, won the race in walkovers, with no opposition at all.

All of this was glorious, but it could not last. What does?

Just as the advent of the Breeders’ Cup in 1984 spelled doom for hallowed events like the famous Washington International turf race at Laurel Park and a dimming of glory for the Jockey Club Gold Cup at Belmont Park, so too came other races for the Pimlico Special.

The creation of the Woodward Stakes in 1954 and other big handicap races at Belmont took the starch out of the Special, especially when Pimlico’s opening day moved to late November, when major campaigns were done and horses set loose in fields for the winter. Suddenly the Special’s stars were no longer so bright, with winners Helioscope, Sailor, Summer Tan, Promised Land and Vertex not quite quickening the pulse.

According to the Daily Racing Form, the 1959 Pimlico Special was scheduled for Nov. 28, “but there were no takers. What had been the world’s greatest Special ended with a whimper.”

The race, though, wasn’t laid to rest, only placed in suspended animation. As the Form noted, “Pimlico officials, however, proved prescient. The announcement that ended the Special in 1958 said, ‘We have discontinued the Special with the proviso it will be reinstated any time conditions call for a special championship event.’”

***

Twenty-eight years passed, and under the dynamic and innovative leadership of Maryland Jockey Club President Frank J. De Francis, and his partners Bob and Tom Manfuso, racing in the state was booming.

These days, bettors take for granted the ubiquity of wagering opportunities. They can go to the track and have some good fun, or they can stay home and bet on laptop computers while in their pajamas. If they want to play races in Hong Kong or Australia, they just need an online wagering account and the constitution to stay up late.

Yet, back in 1987, the Maryland General Assembly said no to a proposal for something as mundane as allowing fans at Laurel to bet on races at Pimlico and vice versa. The future had not yet arrived.

The Maryland Racing Commission, however, heard the pleading of De Francis, bypassed the legislature, and approved intertrack wagering for a one-year trial.

De Francis, a relentless promoter, had bought Pimlico the year before and was looking for something to spice up the spring meet by filling the two-week gap between the Kentucky Derby and Preakness.

Barry Weisbord, president of Matchmaker Racing Services and a long-time racing innovator in his own right, got the ball rolling. He zeroed in on the fact that between the Oaklawn Handicap in mid-April and Hollywood Gold Cup in late June there was no major distance race for older runners.

“It took place after Barry Weisbord met with me over coffee at a time when we were discussing the International,” De Francis told the Evening Sun on May 13, 1988. “He mentioned we might bring back the Triple Crown horses [from the prior year] in the spring. From that point on, the idea developed like a beautiful flower coming into bloom.”

De Francis planned to call the race the Pimlico Handicap, but Tim Capps, who ran day-to-day operations at Pimlico, was a history buff, and he rediscovered, dusted off and sold to his boss a revival of the once glittering prize – the Pimlico Special.

Suddenly, the race was on. De Francis knew the reconstituted Special needed to come out of the gate fast, so he made the initial purse $500,000 with a $100,000 bonus to any winning horse who had been nominated to the Triple Crown as a 3-year-old. He got ABC Sports to televise it.

Fifty years after “The Race of the Century” between Seabiscuit and War Admiral, the Special was back, and the response by the country’s top horsemen was overwhelming.

The biggest star in racing, the 1987 Kentucky Derby and Preakness winner Alysheba, signed on as did Bet Twice, his vanquisher in the Belmont Stakes. Handicap ace Lost Code would join them, along with Cryptoclearance, Lac Ouimet and Maryland’s beloved “blue-collar worker” Little Bold John.

Lost Code’s owner Don Levinson lived in Baltimore, adding local color, and the horse’s trainer Bill Donovan boasted, “If my horse wins, he’s the champion. Whoever wins this has got to be the champ.”

It was only May, but even before the gate opened, the revived Pimlico Special was an instant classic. The high drama of the actual race made it even more so.

Alysheba went off as the 8-5 favorite, but it was Bet Twice and Lost Code who dramatically locked together in combat through the stretch, bumping away at each other before Bet Twice pulled away to a one-length victory.

“For seven minutes, the numbers 5 and 6 blinked in unison on Pimlico’s infield tote board,” wrote Vinnie Perrone in The Washington Post.

At 5:20 p.m., the stewards disallowed jockey Pat Day’s objection, and Bet Twice had won.

“De Francis and the Manfusos have created almost overnight a championship event in the tradition of legendary track operators Col. Matt Winn and Marge Everett,” Ross Peddicord wrote in The Sun.

One year later, De Francis was gone, dead of a heart attack at age 62. Even Vanderbilt, who continued to attend morning workouts and races at Saratoga into the 1990s despite blindness, outlived him. Yet, at least for the Pimlico Special, his work had been done.

The ensuing Specials were spellbinding, aesthetic thrillers. Calumet Farm returned to win in 1990 with the D. Wayne Lukas-trained Criminal Type. The following year, Lukas struck again when Farma Way won in a stunning time of 1:52.40. Then came Derby hero Strike the Gold and Devil His Due and the great Cigar and the lovable Skip Away and Include, from the local barn of Spectacular Bid’s trainer Bud Delp.

Between 1990 and 2006, five winners of the Special – Criminal Type (1990), Cigar (1995), Skip Away (1998), Mineshaft (2003) and Invasor (2006) – were crowned Horse of the Year.

The Special’s restoration was complete, yet racing fell on hard times. Internal and external economic pressures on the game were changing racing’s landscape. The Maryland Jockey Club didn’t card the Special in 2002 and canceled it again in 2007. When it went dormant from 2009 to 2011, the race lost its Grade I status.

In 2012, The Stronach Group (now 1/ST) gamely revived the Special and has run it ever since. Now it’s on the same weekend as the Preakness to enhance a Black Eyed-Susan Day card already brimming with stakes races.

Another class of outstanding older horses will be in the starting gate, and racing lovers with an appreciation for history can close their eyes and summon visions of the wondrous Special winners of the past. So, too, its visionary creator.

“If there is a thread,” the historian Veitch said, “it’s Mr. Vanderbilt. So much of racing has been fractured, but that’s a subject for another day. When the race comes up Friday, Mr. Vanderbilt will be on my mind.”

Story by John Scheinman

Photo Courtesy National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame